What is the Value of a Place?

Restlessness was the hallmark of a decade. In front of us always were the questions: what next? where? We rambled through apartments, neighborhoods, cities, states, following the spinal cord of U.S. 1 or I-95 up and down the east coast of our country, never quite settling in or slowing down.

The last five years in the same house, one we pay a mortgage not rent to live in, have itched with a current of dissatisfaction with its stillness. The sameness of my morning commute: the bus stop, my neighbors who wait there with me every morning whose names I still don’t know, the eerily enforced silence of the route into the city, the dim rhythm of the yellow lights in the tunnel, the angry and reluctant squeeze of the subway cars. All the rooms in our house we rarely occupy; the one IKEA love seat in the kitchen we’re likely to squeeze five people onto at once; the trellises behind the house that drew us, in spring, to buy it; my swing from inattention to attack on the vines that eat our fences leaving a scar when I yanked too hard and my arm found a metal spike.

It is a lonely occupation of a place, despite six humans and three cats residing under the same roof. Despite half a decade of walking down this Main Street, it doesn’t feel mine at all the way the one I knew in high school – just the last two years of it in fact – felt like a territory conquered. There, then, every storefront was a story I’d written or would write. My parents were prioprietors. I stood behind a counter with an index card box of files making credit decisions for the month’s prescriptions the same way the bank on the opposite corner gave me a loan for a red pickup because I was buying it from my dentist’s wife.

How is it that those two, three years gave me possession of a place when here, now I hardly feel the right to claim as mine? Was the bless-your-heart warmth of the South so distinct from the ambition of the City, the suburban shame of living across the River from it? Is the duality of my work/home divide, created in part by that river, such an opposition to the immersion of work/school/church I knew then? Is it that the unity of place then is the antithesis of being a mother/wife and “executive?” Is it the staying-puttness that led women (me, even, for a time) to graduate, go away to school, and then come back to the same classrooms to stand in front of them and teach that is at such odds with the striving, being drawn to elsewhere always, despite not knowing where elsewhere might be?

What is the value of a place? How does it fit who and where you are in life? Or mold you to it? Both?

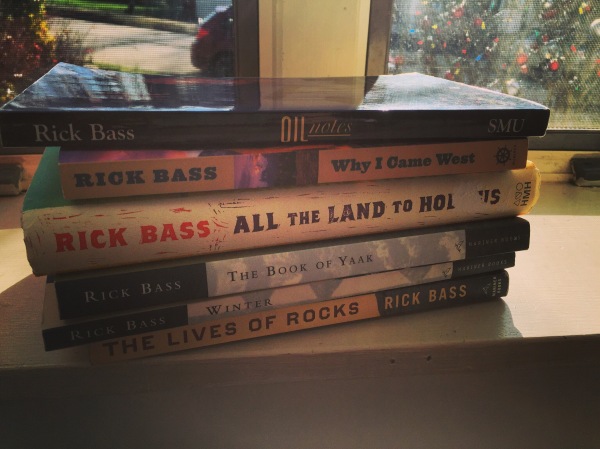

Rick Bass, who I’m reading with a thirst for words I’d somehow forgotten I had, was a geologist before he was a writer. Sediment and rock still lend permanence, real or imagined, to his work on the page. I’m following him into Montana’s Yaak Valley this week. I hope to understand how place has found, riven, and inundated the fissures within me. I hope to quell (or perhaps succumb to) the restlessness. To remember how to belong.

Breaststroke

When I swim breaststroke, my right knee drags behind, some malformation that corrective shoes couldn’t correct disqualifying me. I used to swim on a team, Saturday meets I never thought of as races because I wasn’t going to win anything, just making my cool way from one wall to the other and back again.

I was working up heat under my swim cap, the rhythm of my breath and the strokes taking me forward toward that final touch on the wall that wouldn’t be followed by turning and pushing off with my feet. That was the one where I could strip off the blue rubber cap I’d dipped below the surface to add a bit of water to then stretched over my chlorine-bleached hair.

I wasn’t a good swimmer; I wasn’t fast. I suppose I was steady. I showed up, won Most Improved one season, Most Dedicated the next. Every winter day after school and all summer, I dove off the starting block, the muffled echoes of splashes and voices to my left and my right, then just me for an hour, mostly underwater.

Swimming breaststroke, my body glided or sometimes lurched up, and my hands, drawn together like the blessing before a meal, reached into the water ahead. My legs kicked apart from each other, syncopated. When I let go into the stroke, it was a feeling like a wave, fluid, and I was both riding it and making it, creating wake behind me, unaware of everything – the suction of plastic goggles pressed to my eyes, the drag of the second cement-picked suit the coach told me to wear during practice so I could to feel faster on meet days, other swimmers, sound, time. There was only forward, following the black line at the bottom of the pool, only touching, turning, doing it again.

My body could move more quickly through the water if I pushed it, if I looked up at the clock every other leg to check the second hand. My right knee could do what it was supposed to — kick out like a frog, like my left knee keeping me in contention for something — if I spent all my attention on sending it the proper instructions: up-out-together, up-out-together, up-out-together.

I didn’t, though. I was racing against no one. I wasn’t even racing. I was washing my mind clean, purging myself of thought, feeling, past, present, future. I was earning the cool rush of water over my head at the end of practice when I removed my cap and leaned back slowly, baptized again by my own hands.

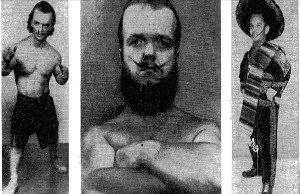

Troupe of Midget Wrestlers Won’t Work for Small Change

Photo credit: New York Times, November 30, 1958

Photo credit: New York Times, November 30, 1958

I’ve been binge reading Gay Talese for weeks now, and tonight I reached new lows, or highs, depending on how you look at it. My commute this week has been filled with his 2006 memoir, A Writer’s Life, but tonight, I cracked open “TimesMachine,” the New York Times archive, which stretches all the way back to 1851. Fortunately for me, my storytelling hero of the moment wrote what looks from the search results like over 1,000 articles in his decade-plus tenure at the Times. For those without an all-access pass to the archives, here’s an excerpt from an article whose headline screamed clickbait long before clicks were even a thing.

What I love about Talese is how he notices things. He is so specific, and in his precision an “eight-inch extension onto the brake” is something you know, have always known, even though of course no one has paid the slightest attention to it before. It is a craft, this ability to get it right, to sift through all the possible images to paint the one that has meaning. I have been honing this ability at work over the last 18 months, and my whetsone is my colleague and friend Roy, who never lets (me let) go of the craft. Even when something feels finished, he finds the places it isn’t and whittles them away. I find myself quoting Proverbs when I think of how his noticing things echoes how I feel reading Gay Talese: it makes me better at what I do.

“Iron sharpeneth iron; so a man sharpeneth the countenance of his friend.” Proverbs 27:17

“

Piece of Cake

On top of the gear shift between Reggie and I was a styrofoam take-out box, and inside it was a piece of cake.

“Have some cake,” Reggie said. “It’s good.”

“No, thank you,” I said.

“It’s cake,” somebody said from the back seat. “Have some.”

I know it was after two because the place we’d gone to with the go-go dancers up above us in cages had already closed down. It might have been after three because we’d spent a real long time getting from coat check out the door and over to the bar with the jazz band that started packing up just as we sat down for a plate of wings. That must be where Reggie got the cake.

“Fine,” I said. I reached over and slid my thumb up under the lip of the box. It popped, slid, squeaked, and the lid sprang open. There was the cake.

Reggie was still parked, I think, when I pinched off the top layer and the caramel that stuck to either side. Only a few crumbs dropped past my knee onto the floorboard of his car when I licked the frosting off my fingers.

Reggie was right. It was good cake.

Time Flies

“Look. A plane,” my son whispered. There’s a skylight over his bed, and since the trees are bare for winter we could see the lights on an airplane that must have taken off from Newark Airport a few minutes before.

His room was dark except for the corner where he’d switched on the nightlight. He and I were nearly nose to nose on pillows, nestled under a blue blanket featuring a llama that his Abuelos brought us from Ecuador and a green and brown afghan crocheted by my Nana when I was a kid. Under his pillow was a stain from a nosebleed he had two nights before. I had meant to change the sheet, but I forgot.

“Oh, cool,” I said, catching the tail lights of the plane and hearing its afterwhoosh overhead. I listened to the sounds of the frozen branches creaking against the siding and the radiator gurgling in the walls. A train rolled by a few blocks away and its whistle blared. Night noises. Soon I figured I’d hear him breathing when he finally fell asleep.

“I’m probably going to London in a couple of weeks,” I’d said at dinner.

“Lucky,” he’d said.

“Why did you say I was lucky because I’m going to London?” I asked him when the plane had passed.

“Because,” he said, “they have a lot of fancy hotels there. And cool museums. They have Big Ben.”

“I saw Big Ben last time I was there,” I said. “But from kind of far away. I didn’t go to any museums though. Would you like to go to London some time?” I asked.

“Maybe,” he said. “Well, no. It depends. Would I go in a plane?”

“Yes,” I said. A boat would take too long.

“I only want to go in a plane if I can sit in the fancy part,” he said.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“You know, the part where they bring you dinner and take good care of you,” he said. He rolled over for a minute, flipped his pillow to the cool side, waited for me to respond.

I didn’t know how to, because I was wondering if he was getting his notion of flying from stories I’d told at the table, or from watching Home Alone.

I didn’t say anything, so he asked, “Do you fly in the fancy part of the plane?”

“It depends,” I said.

“On what?” he asked.

“Where I’m going. If I’m flying for work or with our family. How long the trip is. If I’m flying overnight and sleeping on the plane,” I said.

“What’s the longest plane trip you’ve ever taken?” he asked.

“Eighteen hours,” I said.

“Eighteen hours! That’s six hours more than half a day!” he said.

“It is,” I said, never having calculated it quite like that.

“Where were you going?” he asked.

“Asia,” I said. “Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong. Do you remember that trip, not last summer but the one before?”

“Oh, yeah,” he said. “That was a long trip. I don’t like when you go on long trips. Two or three days is okay, I guess, but when you go for a long time, it’s not good.”

“Well, if it takes almost a whole day to get there,” I started to say, but he interrupted.

“Did you fly clockwise or counterclockwise?” he asked.

I held up my left hand in a fist, blocking the skylight and the swaying trees. My right hand became the plane flying around the tiny fisted Earth. “Do you mean did I go this way?” I moved west across the expanse of North America and an imaginary Pacific. “Or this way?” I flew the tiny business class passengers in their lie-flat seats with their hot lavender towels and complimentary champagne and orange juice over Africa and the Indian Ocean instead.

“Yeah,” he said. “Clockwise or counterclockwise?”

“Well, a clock is a circle,” I said, joining the two mirrored Cs of my thumbs and index fingers together above us. “So you can go this way” and I indicated going one way with the tip of my nose. “Or that way” and went the other way. “But the Earth is a sphere,” I said, and I reformed my tiny planet. “So really you can go around it to the other side almost any way you want to,” and I made a dozen rapid orbit paths over Russia, over Greenland, over Chile, more.

“But which one is safest?” he asked, turning to look at me again. There was the little boy this summer who overheard too much NPR in the backseat and told me I can’t go to Nigeria because of Ebola.

“They’re the same,” I said, brushing his hair across his forehead. “Once you’re up above the clouds it doesn’t make a difference.”

“Oh,” he said, and I saw the even littler version of him that my sister always remembers, the one who said “Why?” again and again until some reason you gave suited him and he just said “Oh” and then left his lips in the shape of a clock long after the sound had gone.

I had loved that small boy so much I’d thought it was all the love I had. But the capacity for love is as endless as the paths I could take to get around the world, or the ones he could choose to who he will become. He is still a boy who wonders. I wonder, too: at him, at being his mother, at having the sort of job that puts me on planes that fly to the other side of the Earth, at how to love all of it without missing any of it.

“Why did the boy throw the clock out the window?” he asked me, trying on a joke he’d heard at school.

“Why? I asked, even though I know.

“To see if time flies.”

What Cheer

Lately I feel a little bit like The Joe Biden Random Compliment Generator: real and not real, slightly disturbing but possibly a little bit brilliant all at the same time. This holiday season, several people I care about have said in all seriousness, in one form or another, “Angie, I need you to cheer me up.” And, one way or another, I have.

There’s something about the request that feels both vulnerable and bold, false and transparent, needy and giving. Asking to be cheered up requires confession. You confess to me you are lacking; I admit to you I am willing and able to play at, and with, happiness in the hopes of creating the real thing in you. You reveal your hurt, your dispiritedness; I conceal my doubt that I can make it, or you, better.

You need me. I enjoy being needed, and then I do the best I can to meet that need – both in the hopes you’ll no longer need me and also, if I’m truthful, in the hopes it will be me you need the next time you feel this way again.

Whether I’m across a desk or the dining room table or somewhere on the other side of the country, we are both getting something out of this arrangement. You know that don’t you? I hope so. Then again, maybe I don’t.

What is cheer, then, holiday or otherwise, but the most generous and most selfish gift we give?

Happy New Year to those whose spirits I’ve somehow managed to lift. You’ve lifted mine, too.

Detroit Hustles Harder

A year ago, I started chasing a story about Detroit. I dogged the bankers who were working on the deal until they relented, determined to make a film about the lights coming back on in the Motor City.

Last week, we made that story. Last week, a security guard in a bronze two-door Fleetwood followed us up Woodward and over to Corktown, up and down the now bright streets parking under the LED lights to keep watch over our equipment, over us. He didn’t say a word when I knelt down and stole a picture of the insignia on the side mirror of his car. He didn’t know I’d grown up in the back seat of a long succession of cars just like that one, curling up in blankets on the wide floorboards on long drives.

Ruin porn wasn’t what I was interested in us making. I’d fended off enough of that in New Orleans in the aftermath of Katrina as a Red Cross worker the day families went back to their ruined homes in the Ninth Ward for the first time. I had been the one responsible for keeping watch over the cameras then: news crews from all over the planet chasing a story just like I’d now come to Detroit to do.

As we drove out of the sections of downtown where signs of life were more than evident, on our way to the old power plant to shoot a scene, the empty and burnt-out houses we passed made it clear the rest of the city is still firmly in the middle of its own aftermath. It reminded me of driving around the levees in Louisiana trying to spot the sources of the leaks.

Last week, we, the storytellers, sat in an abandoned building in front of a push-pin and string map that until last year was how Detroit managed the city’s streetlights. We sat in a row of folding chairs with headsets on and we monitored the monitors and listened for soundbites as the director asked the same questions again and again. I raised both my arms with both my thumbs up when I heard a good one, locking eyes with my co-creators of this story when we knew we’d gotten what we needed. My own earnestness punched me hard at one point with the belief we were doing more than making a tv commercial: we were recording history. Possibly we were.

“If no one tells the stories,” I said later at dinner, feeling noble and full of purpose as I sat next to a guy who’d written legislation to make the whole idea we were filming possible, “only the people who experience them will ever feel the hope they provide.” But while I was making a film the day before, he’d been making sure legislation passed so tens of thousands of abandoned buildings would come down. I could only listen as the people around me who lived here, who led this city, spoke with real passion about police response times, school buildings, what was next.

I was experiencing this story, standing in the cold with tiny balls of sleet bouncing off my giant purple coat. I was an urban explorer peering down at massive and dormant machinery marked “not for sale.” I was me in the back of my dad’s Cadillac again as we rode the glass elevator to dinner on the 72nd floor of the building where it had been designed.

“Detroit hustles harder,” a sticker on our equipment cart read. I looked for one at the airport gift shop on my way home.

We captured the story I’d hustled so hard to get us to make in Detroit. Rather, we constructed it by choreographing extras walking up stairs, down sidewalks, across parapets, along the riverfront. By interviewing government officials, musicians, bankers, retired cops, nurses, moms who are starting to feel a sense of hope.

I just hope we do it justice.

Buttermilk

“The refugee experience of dislocation, cultural bereavement, confusion and constant change will soon be all our experience. As the world becomes globalized, we’ll all be searching for home.”

— Mary Pipher, The Middle of Everywhere.

For a long time my mother was just about the only person I knew who drank buttermilk. I remember her telling me how she’d hold her nose and gulp down a tall glass of it when she was pregnant with me, just to strengthen our bones.

When I was in high school, she’d have it in a thick glass encircled with red and green stripes with a couple of pieces of cornbread crumbled in and shoved to the bottom with a large spoon. She’d eat the soaked cornbread with the same spoon and then drink the buttermilk that grated her throat with its tiny leftover crumbs.

I know how it felt because sometimes I make my own version of this East Tennessee cocktail. I fill up one of my own glasses with warm cornbread right out of the oven and pour cold whole milk over it like a bowl of cereal. I eat it with a small spoon, crushing down the cornbread that has soaked up the milk like a dishtowel, and then eat it like my grandmother did after she’d taken out her teeth.

Grannie was good at cornbread, and we’d make it in the kitchen of her trailer while a pot of pinto beans simmered on the stove. I’d simmer too, roasting the back of my legs in front of her big gas furnace and then turning around to warm the front side, too.

She had a big tank of gas out back that I longed to ride like a cowgirl. It was next to the old house my mom had partly grown up in, beside which sat a school bus full of furniture my uncle had left when the Army moved them across the sea.

A couple hundred yards down the family property sat two other trailers, one a rusty red and the other a faded white. Uncle Raymond and Aunt Nettie lived in the white one, and their collection of, well, everything, spilled off the screened porch and into the yard. My parents owned the red trailer, but we never lived there, just used it for a few years when we came up for weekends and then rented it out to aunts and cousins who made it a more permanent home. Out back was the old road my grandfather had ridden his horse cart through alongside the creek. It was where my Daddy taught me to shoot a gun by setting an rusty can of Dr. Pepper up on the sawed off stump of a tree.

I still buy buttermilk, usually when I feel like making cornbread. Despite watching Grannie and then my Momma make it a hundred times, I still measure out the ingredients according to the recipe on the back of the cornmeal bag I buy at the grocery store. Even when I’ve got the Merle Haggard station I created playing in the background on Pandora on my iPhone, it almost never turns out right.

My husband is forgiving, and sometimes this makes me think less of him. Not him, really, but his ability to understand me and my need to be able to make good cornbread. I know he wants to make me feel better, but telling me the cornbread is good when it just isn’t makes things worse, even more so when he believes what he’s saying is true.

I think his mother understands something about cornbread, about buttermilk. Like mine she was not raised in the city or the suburbs. She understands what it means to drink milk warm and straight from the bucket that sat underneath the cow. I don’t. He doesn’t. But I bought us a cast iron skillet at the Salvation Army and cured it with bacon grease in the oven just like my Momma told me I should.

His mother can feel beyond the crisp crust. I think she understands the need for the texture of home. I say it this way because her English and my Spanish keep us at safe distance from such intimate exchanges about food.

I sometimes wonder, sitting across the table she insists on clearing when I’m the one who has prepared dinner, how it came to be that she and I are connected by the thread of a boy who sits next to her not finishing the home fried potatoes I’d decided not to peel.

I think back to a single day in a $500 two-bedroom apartment in Buford, Georgia, a girl on the brink of puberty, almost able to speak English because I’d been teaching her, knowing just enough to tell me they’d left her grandmother behind.

I was 21, hadn’t even finished college, had moved back home for my last year as an English major, and had needed a job. I’d called up my high school principal, also a deacon at my church, who’d told me they’d gotten a grant and asked me if I was interested in teaching.

I hadn’t thought much about teaching, wasn’t getting a teaching certificate, but I’d just completed a course at the Statesboro library on how to teach literacy and thought that his offer might be a place to begin.

My mom was, for the first time in decades, making cornbread in her own kitchen in a basement apartment on the other side of the city. I was wading through what that meant with my sister, my father, in our house by the lake in Buford.

The town had changed in the few years since I’d left it, and this teaching opportunity was evidence of that. I had graduated with exactly one Latino, and now the elementary and middle schools were over 20 percent non-native speakers, as I learned they were called.

Dijana was one of my middle school students, and she was more than a head taller than the short Mexican girls with long braided hair who sat with me in borrowed classrooms. Dijana was loud, funny, quick, and Bosnian. She lived with her family in an apartment behind the supermarket near the highway. That grocery store was called Ingles – Een -gulls, we pronounced it, not having any idea that to many of the immigrant students who were moving into town it meant English, the language I was hoping they might learn.

I didn’t have anyone to tell me whether it was appropriate to accept Dijana’s invitation, but she made it so often, and so convincingly, that eventually I did. I drove into her complex in my red Chevy S-10 pickup and saw several of my students playing in the parking lot, watching their siblings ride second-hand tricycles on the asphalt in the heat.

“Come in,” Dijana’s mother said, and it was soon clear that these were most of the few words of English she’d been able to acquire in the classes she’d squeezed in at the Presbyterian church a few blocks away.

They were Muslim, and thinking back now they were probably the first Muslims I ever encountered, surely the first whose home I’d ever walked into, the first who’d invited me in.

I sat down on the sofa, and it seems now it should have been covered with something, a comforter maybe, or possibly even a clear plastic covering that perfectly fit over the contours of the cushions, the arms,and the back. Just like the one my mother-in-law uses to keep the dust off the furniture in their home in Ecuador, it must have squeaked when I sat down.

Drive around I-285, the perimeter that once encircled the whole city of Atlanta, provided some sort of boundary for it, and you’ll see trees, lots, small forests draped with invasive vines. In summer, they make the shoulders of the roads so green you feel a freshness amidst the heavy humidity. In the winter, such as it is in the South, the brown vines are exposed as creeping and ominous, weaving in and out of branches from the rusty barriers of the highway to the backyards of the nearest homes.

Kudzu is considered a nuisance, and every time we pass a large patch, my father reminds me of his version of its history, claiming it was brought over from Japan to stop erosion and ended up causing more problems than it solved. He says it is impossible to kill. You can hack it, burn it, freeze it, trim it back, yet it survives, becoming impenetrable eventually.

It was growing up the wall in Dijana’s family’s apartment, creeping up from floor to ceiling on a series of nails. Its tendrils were reaching from the black and gold entertainment center to the front window’s sunlight, unstoppable.

I sat on the sofa as hearty smells wafted in from the open door at the far end of the kitchen. Dijana’s mother was grilling on the fire escape. She had a small, charcoal grill with a red dome top, and she knelt down to reach it, to tend its warm flame. Halal meat, something I’d only learn about in the years to come working with other refugee families like hers, was charring on the escape route from their second floor home.

A few minutes later, Dijana’s younger sister, who was eight, brought an almost silver tray with a matching set of china out from the kitchen. I thought of my Nana’s china, lost now, whose cups then hung from hooks and whose plates perched on top of box frames around the picture windows in the dining room and kitchen of my parents’ home. There were two sets, one royal blue and white, sturdier, and the other a delicate bone with pink roses and a gilt trim around the rim.

Dijana’s mother’s china was like that set, with tiny handles you had to pinch between a forefinger and thumb to hold. I wondered briefly if she’d brought it with her from Bosnia, realized that was ridiculous, impossible in the flight from war. As her sister set the tray down on the black coffee table in front of us, Dijana told me about the house they’d lived in back in Bosnia, she told me about her school, their village, the garden her grandmother had tended behind the small concrete home they’d shared.

“All of it gone,” she said, the four simple words I’d given her perfect for the sentiment she needed to share with me. Just her grandmother had been left, and I wondered how she was surviving without her vegetables.

I looked into the cup, thought of my own grandparents’ land, now fallow with a few of their children’s trailers planted in place of corn, tomatoes, cotton. No need any longer for the nine siblings to start school after the harvest was done. Like PawPaw and Grannie alive only in our memories, even the farm house is nearly gone. She’d moved out of it back in the seventies when it became unlivable. When the movers broke some of our furniture in our last relocation, I began to long for some of that hard wood so I could build us a sturdy dining room table.

I looked down into that cup that afternoon, and what I saw was something familiar: white bordering on yellow, thick and creamy with edges bubbling up to the lip of the white China cup into which it had been poured.

I saw my mother, her journey out of poverty and into our kitchen and then her own. I saw Dijana, making her way to my classroom, me making my way to her because my mom had found a way out, if only for a little while, again.

I took a sip, drank down the acrid taste of the buttermilk. I thought of my mother thinking of me growing inside her, taking a breath, and making me strong.

Picture perfect

Since I got a smartphone, I’ve taken thousands of pictures. Over the same seven years or so I’ve also spent a lot of time on photo shoots, and I’ve learned a enough about lighting and composition to get a great family holiday photo in a single take. I’ve picked up enough about editing and filters to make backyard snapshots look like something that might go in a magazine. I’m not claiming expertise, just practice and a basic understanding of what it takes to take a good picture.

What’s freed me up to gain some level of skill and confidence is the room to fail. I’m no longer limited to the 24 shots on a roll of 35 millimeter film or the wait time to get them developed before knowing what I’ve got. Gratification, like iteration, is instant.

It isn’t fair to say I got the holiday shot in a single take. There were actually several, with my son and sister as stand-ins on the spiral staircase. I adjusted curtains, scooted the Christmas tree, raised and lowered my iPhone tripod and set the timer at just enough time for me to get back to my spot but not too long that my family couldn’t hold their smiles.

When we were kids, my dad never said, ” Say cheese.” He said, “Say bartsfarkle,” which made us laugh instead of smile. He also seemed to never break out the camera except on Christmas morning, when I was barely awake and none of us had brushed our hair. It’s funny to look through photo albums and see the same pictures over and over again: us surrounded by wrapping paper, curled up in a big green chair or holding a gift up to the camera from the living room floor.

My dad took decent pictures, but whether they were birthday parties or Easter morning, there’s the quality of occasion to all of them. Dressed up or still in our pjs, on vacation or at a piano recital, there was something about the moments that were photographed then that was apart from the rest of our lives, frozen even as they were happening.

We rarely print pictures these days, but there are some photo albums from my post-college era that have captured my daughter’s imagination lately. “Who’s that, Mama?” she asks, pointing at friends and former students whose names I can’t always recall.

She was “Star of the Week” a few weeks back and we were asked to bring photos to put up on the bulletin board of her. I chose pictures of her doing favorite her favorite everyday things: riding a horse at Van Saun Park, hugging our cat, playing in the sprinkler, reading a book. I also chose the classic hands-in-the-birthday cake shot from when she turned one, a moment conceived and constructed for her, as it had been for me, solely for the purpose of taking that photograph.

As I was choosing which images to print and share, I scrolled through more than 3,000 of her and my son, images we’d taken since she was making my belly the size of the pumpkin on the table next to me at the pick-your-own farm. So many of them had been shared with friends on Facebook that I was able to print the ones we needed by logging in to my account from a kiosk at my local CVS. I put them all in an album yesterday, and tonight we sat in the orange chair while she explained to me what each of them was.

I wondered what the ability to document everything in images has done. Are we more likely to capture the everyday? Or have we curated all of our moments into miniature occasions? Are our pictures more reflective of what we experience since we know better how to make the photos in our phones match the snapshots of our memories? Are photos now proxy for memories, or have they always been?

I’m not sure, but tonight I read an article about how shelter pets who have been waiting for forever families for months are getting adopted within hours of a good photo of them being taken and posted online.

It is the same sort of curated authenticity and instant intimacy that is perfected in Instagram feeds and that make us feel like we know the kids of our high school friends, people we haven’t actually seen since graduation. The simple tricks of perspective, backgrounds, tonality – and the freedom to take as many shots as needed to get it right – hold promise beyond perfecting the holiday portrait or portraying the perfect family, and they’re saving animals lives.

As I was putting Nacine to sleep tonight, I told her the story of Rascal, the stray cat we brought in to our basement who had kittens in a laundry basket. Rascal nursed and weaned them and they opened their tiny kitten eyes in a refrigerator box filled with our old sheets and towels and then promptly left our lives the way she’d entered through a screened door. I wondered if I remembered the story itself so vividly or if it was the photos we’d taken of baby Tit-Tat and her brothers and sisters that cemented the memory there so I could share it tonight.

Either way, I think, pictures hold power: to turn moments to memory and memories into moments again.

What a picture is worth

Last week I heard about Getty’s new Lean in Collection on my local NPR station, WNYC. I listened to the story about pictures with my communications person hat on, thinking how frustrating it is to try and find good stock images of anything but especially of real people – women, diverse ethnic groups, humans that don’t appear to be androids. Today I saw the story again, this time on Buzzfeed, and perhaps because I was seeing a sampling of the photos themselves, the story resonated with me on multiple levels. Not just as a mom in her thirties with biracial children. And not just as someone who often tries to represent a brand and communicate a message through photography. But also as a person concerned about social issues like women’s rights and how brands and companies address them intentionally and also through their business activities. Here are a few of my takeaways of why this initiative is so great:

- The images are visually stunning and fill a void in the marketplace.

- The pictures reflect the world as it is, and don’t make a preachy fuss about social change.

- The pictures cut across generations, and depending on yours you either see your normal finally depicted or stereotypes you’ve long fought being broken down.

- It’s not positioned as an announcement about a partnership or grant funding, but the end product shared with the world as a useful thing.

- The publicity isn’t just about promised collaboration but instead informs both the niche of potential users but also manages to matter to everyday women.

- It is dead center of what Getty does as a business and addresses a globally relevant social issue.

- It is going to make people think AND it will undoubtedly sell more images for Getty.